Fukushima Radioactive Zone

In the aftermath of the The Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011, the Japanese government established an evacuation zone around the damaged nuclear reactors of Fukushima Daiichi.

“Cesium Tours” is a visual study of the radioactive wasteland around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, one year after the melt down.

The images shown were taken at various locations between 22 kilometers and 16 kilometers from the the damaged reactors. Access beyond the inner 20 kilometer perimeter is forbidden by the Japanese government and trespassing may be considered a criminal offense.

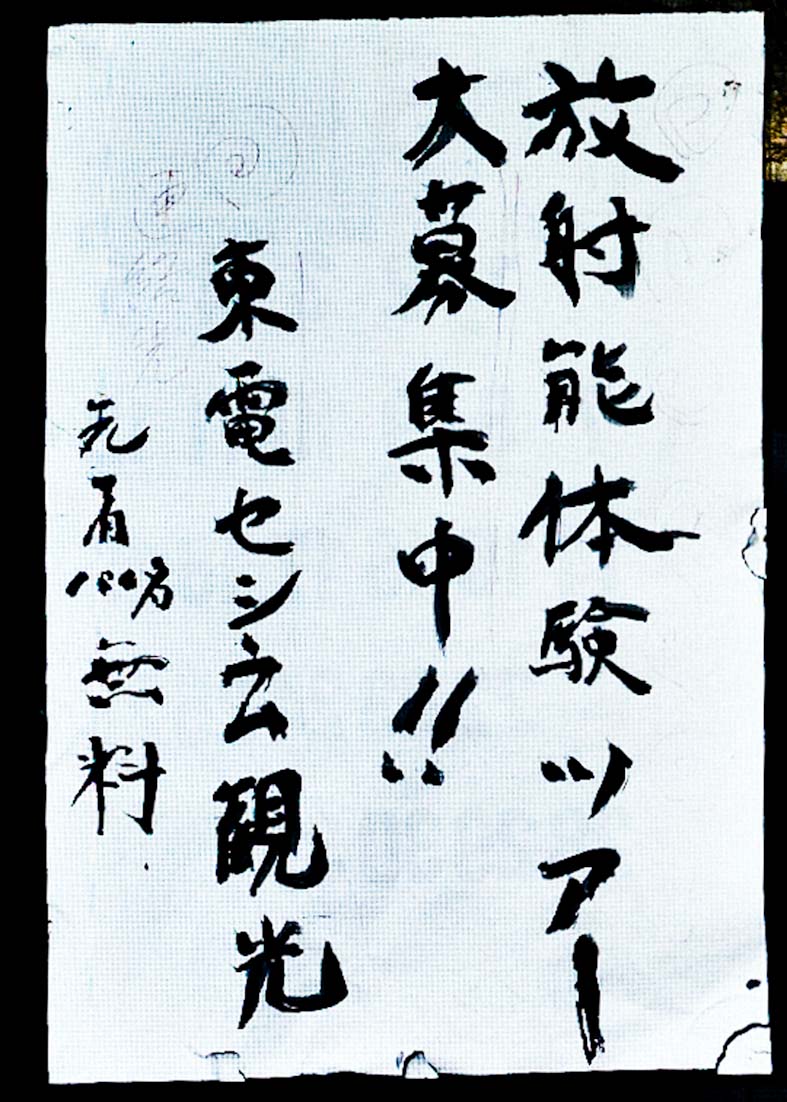

Residents Protest – Fukushima One Year Later

“To the townspeople of Tsushima District: This is a message from Namiecho City. We are looking for tourists to join our radiation tour! Free for the first 100 who sign-up! -TEPCO Cesium Tourism Association”

( Sarcasm as a form of protest is rare in Japan. Protesting itself is rare. Frustration with TEPCO and the Japanese government has pushed evacuated families to break with social tradition and voice their anger in notes left behind on the windows of their homes. )

Evidence of Earthquake and Tsunami – Fukushima One Year Later

Although many areas are now cleared of debris, there is still ample evidence of a violent culmination of events, and an interruption of lives. A thick layer of sand and sea sediment covers the damaged areas. In some places the smell of rotting fish is still strong.

In areas contaminated by the radiation from the Fukushima Daiichi, there is comparatively little physical damage. Buildings are left standing, but being radioactive, are really just debris. Radiation is invisible and odorless.

Rather than violently interrupted, human life–and only human life–feels abruptly absent, as if it were removed in the middle of doing something ordinary. Habitation will not resume, but a hanging feeling remains that thousands of mundane actions are poised to suddenly resume.

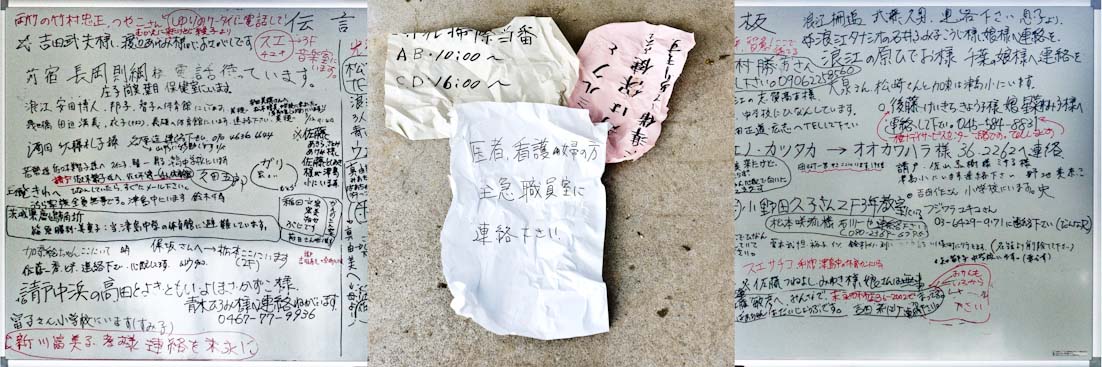

Evidence of Evacuations – Fukushima One Year Later

Schools in eastern Fukushima prefecture were used as evacuation centers. Relatives left notes to each other, and public notices were posted on doors:

” …doctors and nurses: Please contact the office right away. You can get powdered milk, hot water, and adult diapers in the infirmary.”

“…To Tokiwa: if you are OK please contact me right away. Our family is all safe, we’re in Tsushima junior high school- Chihiro Suzuki Ibaraki prefecture Kashima-shi Kadoori. Katsutoshi/Mieko Shinohara: evacuated to the gym in Tsushima junior high shool. To Kanae: Please stay here, Akari…”

Two days after the tsunami, radiation leaks from Fukushima Daiichi forced the relocation of the evacuation centers: “…To Hisao Muto: please contact me, your son…To Tsuneyoshi, Miyuki, your daughter is fine…”

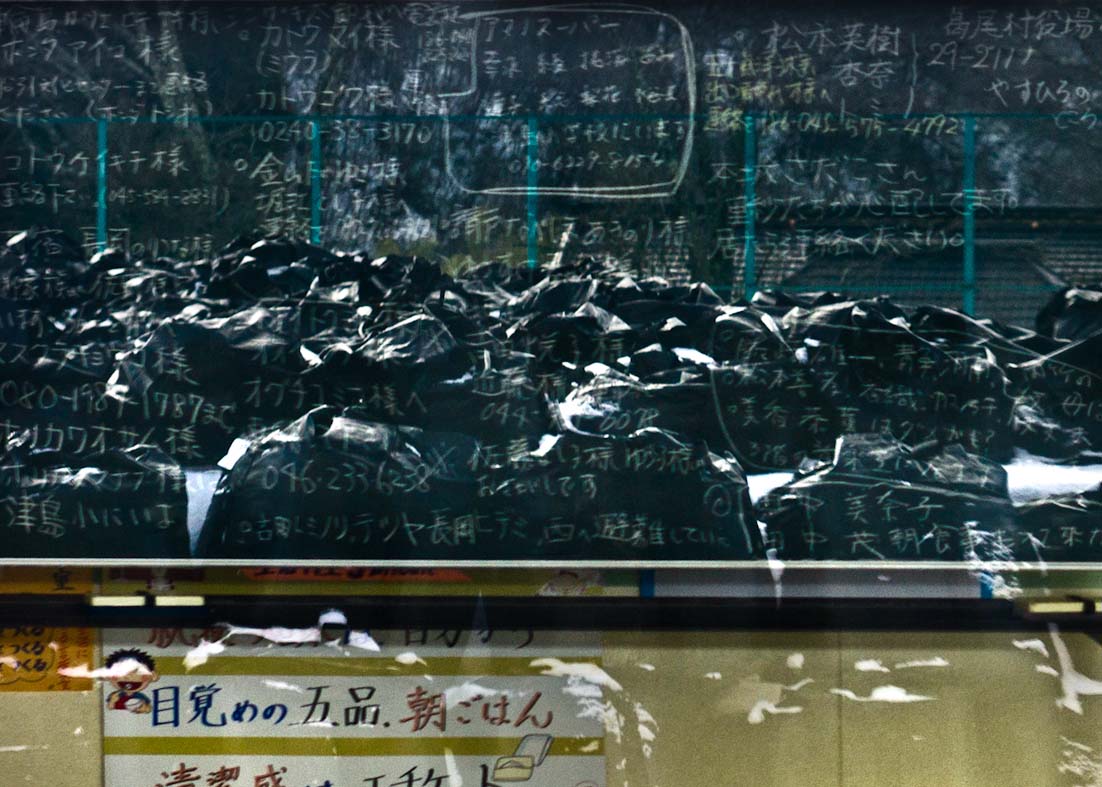

Radioactive Zones – Fukushima One Year Later

One year after the first radioactive leaks, school yards in evacuated towns are used as collection grounds for contaminated soil. The Japanese government has the intent of using the schools again and hires private contractors to decontaminate them. Mr. Onada, a former resident of Futaba notes, “This is really no more than a symbolic act. The government has to show it has done its best effort before admitting defeat and closing the areas forever.” As of January 2012, radiation measuring stations are set-up in these areas. Readings vary widely. This school in Namie registered 0.18 micro sieverts in the northwest corner and 5.4 micro sieverts in the southwest corner.

The Japanese government mandated a forced evacuation in a radius of 20km around Fukushima Daiichi. A further 10km are deemed a voluntary evacuation area. Entry is strictly controled and usually denied to all but former residents. Road blocks and police abound. Many pets are abandoned. The luckiest ones are chained to their homes so they do not run away, with week’s of rations and water left for them at a time.

The voluntary and mandatory zones are not coherently determined on levels of radiation. This may be revised in March 2012. Some towns with low readings have a forced evacuation order imposed, while others with readings of up to 10.9 micro sieverts per hour are deemed voluntary evacuation zones.

“To the townspeople in Tsushima District: This is a message from Namiecho City Hall (Disaster countermeasures office). We are worrying about the dispersal of radioactive substance caused by the nuclear disaster in Fukushima Daiichi. Please evacuate from this City as soon as possible. We decided to establish the temporary Namie City Hall on the 2nd floor of the Towa branch office of Nihonmatsu City Hall. If you want to know where to evacuate or the safety information, please contact to the phone number below (0243462111).”

Minamisoma Town – Fukushima One Year Later

The City of Minamisoma had over 70,000 residents before the disaster. Nearly 1,500 perished in the tsunami. Two-thirds of the residents evacuated in the wake of the nuclear melt-down.

Minamisoma is bisected by both the 30km and 20km evacuation belts. A large part of the area in Minamisoma that was destroyed by the tsunami is within these zones. One year after the disaster, most of the rubble is cleared, but nothing is re-built, leaving it a no-man’s land.

Although technically illegal to enter, the 20km belt in Minamisoma is porous and crossing under cover of darkness is straightforward. “The government is telling us that we will be able to return to our homes, so it makes no sense to keep the evacuated zones closed. They closed them, not because of the radiation, but because there was so much stealing. At night you would see shadows, like coakroaches come out into the streets and in the morning so many things would be missing.” – Mrs. Hoshi, former resident of Minamisoma.

In the inhabited areas of Minamisoma it is rare to see women or children, as most left to safer areas. Volunteer workers, journalists, and TEPCO contractors keep the city’s hotels full, and fill the local bars with drinking and karaoke. A few kilometers away, inside the 20km zone, personal items litter the floor of destroyed homes. “When a damaged home is still standing [as opposed to being razed by government construction crews] it usually means the owner died and his estate is still being resolved.” – Ms. Takahashi, former resident of Minamisoma.

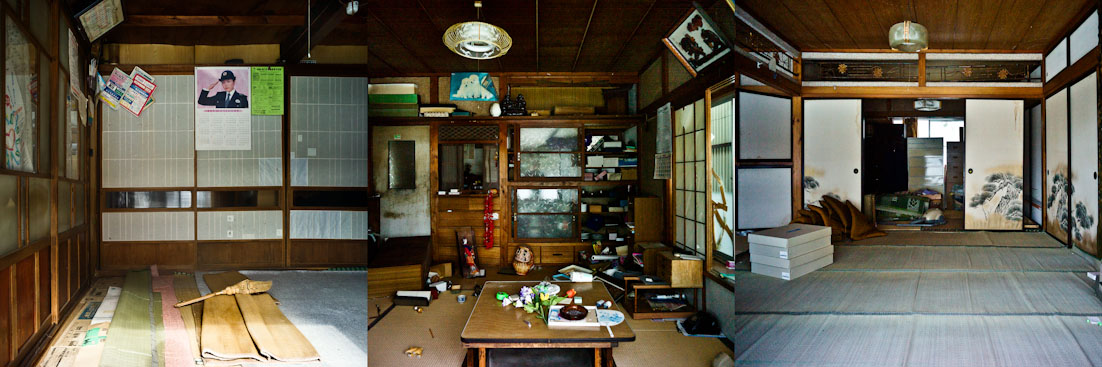

Abandoned Towns – Fukushima One Year Later

Further south of Minamisoma, the towns of Namie and Futaba are under forced evacuation orders. In the parts that were not affected by the tsunami, damage is comparatively light and, without a point of reference, like destroyed buildings, the emptyness is surreal. During the first few months, most homes were left unlocked, but after extensive looting, it is now rare to find any that are open.

“I know it sounds horrible to say, but in a twisted way, the only thing that TEPCO has done is to accelerate what was already happening. We are an aging society and the inhabitants of these towns were already mostly over fifty or sixty years old. They were already becoming ghost towns. This is a small case study of what we can expect to happen all across Japan in the next thirty years.” – Mr. Tadaki, former resident of Itate.

“The government says it will be safe to return, but we don’t believe that. We know that radiation is too high for this to be safe. Maybe for those of us who are old it doesn’t make a difference but the children should not have to come back… It is ironic though that the government has opened new schools in parts of Fukushima City that have higher radiation than the evacuated towns. But no official evacuation order exists for these places, so nothing is done about it.” – Mr. Watanabe, former resident of Itate.

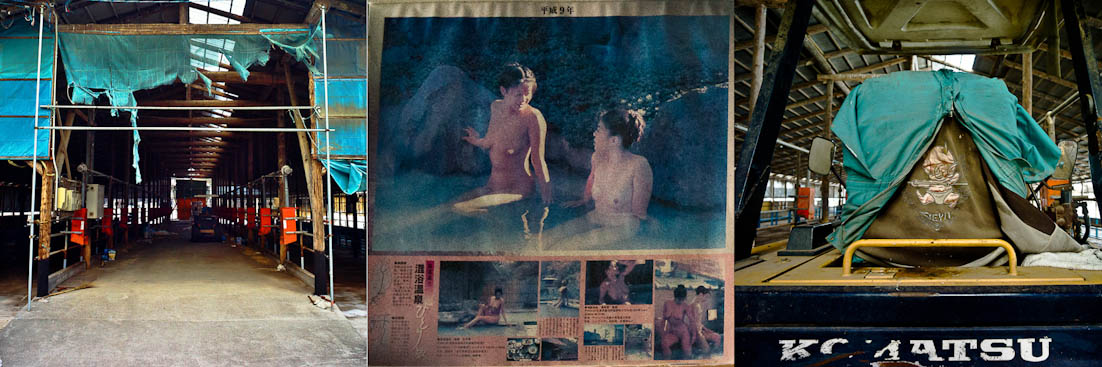

Abandoned Industry – Fukushima One Year Later

“TEPCO is offering us ¥10 million for our homes, and another ¥3 million per person. But it costs us that much to simply move to a new house. It does nothing to address the income we are losing from no longer having our business.” – Mr. Harigaya, former resident of Futaba.

Many towns in Fukushima prefecture had big cattle and dairy operations. In the aftermath of the disaster, thousands of cattle were sacrificed or left to die. A few entrepreneurial farmers keep their cattle alive and buy feed by smuggling journalists into the exclusion zone for $1,500 US per day. “This farm had 1,000 animals. The owner was able to sell the cattle to other farmers in Japan, even though cattle in other [nearby] areas had already been found to have radiation in them. These cattle were not checked for radiation.” – Mr. H.W. former resident of Itate.

A Lost Way of Life – Fukushima One Year Later

Many homes are locked, particularly to dissuade looting. Curtains are closed, and views into homes are often only possible through cracks in windows and rice panel doors.

Agriculture is important in Fukushima, and old barns and homes abound—many still use out-houses and traditional heaters and stoves. Fear of radiation caused Fukishima produce to either be banned from sale, or avoided by consumers. Frequently, farmers feel this is unfair. “Less than one percent of our samples show any radiation levels that are above the health limits.” – Mr. Sato, farmer in Minamisoma. This comes in direct conflict with many of their neighbors, who doubt the official radiation measurements and demand more action from TEPCO and the government.

Many of the abandoned homes in the Fukushima area tucked in among the hills in modest clusters. Most owners return every couple of months to keep their belongings tidy. “I want my wife and me to have a place to die that is ours. That is why we will go back to keep things as orderly as possible until then.” – Mr. Yoshimura, former resident of Namie.

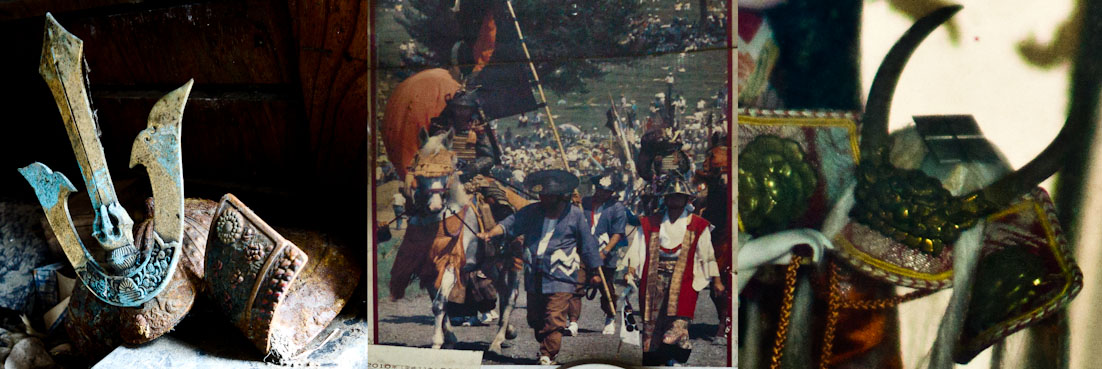

Forgotten Details – Fukushima One Year Later

The Soma District of Fukushima Prefecture is famous for horse-breeding, and the region is historically know as a bastion of Samurai tradition. Both come together every July in an ancient horse race called the Soma-Namaoi. Its origins are in the early 10th Century when samurai warriors secretly commenced military excercises. Wall calendars and decoration commemorating the event are common in the region’s household, as are the decorative kabuto (helmets) that express the hope that each boy in the family will grow up healthy and strong.

The Japanese Doll Festival, or Girls’ Day (Hina Matsuri) is a yearly event, and was held one week before the disaster. In some abandoned homes the dolls are still laid out. The tradition started during the Heian period, when straw dolls were set afloat on a boat and sent down a river to the sea. As they drifted down the river they snared troubles and bad spirits, taking them away with them.

Tanuki is the mischievous Japanese racoon dog who is a shape shifter, and humurous prankster. He wears a hat to protect him from trouble, and his eyes are wide open to see all that is around him and make the best decisions. He walks with a swagger, large testicles between his legs, a sake bottle in one hand, and a promisory note in the other.

“Tan Tan Tanuki no kintama wa, Kaze mo nai no ni, bura bura…” / “Tan-tan-tan, tanuki’s bollocks ring, The wind stops blowing, But they swing, swing, swing…”

Mr. Watanabe sans’s Wish

“I know we cannot live there safely, even if the government says we can. Most of us have accepted this fact.”

“Is there something you would like me to tell people when I show my pictures?”

“We live modestly. I think most people don’t know where we are, so I think it will be difficult. But maybe they will see your work and they will remember us.”

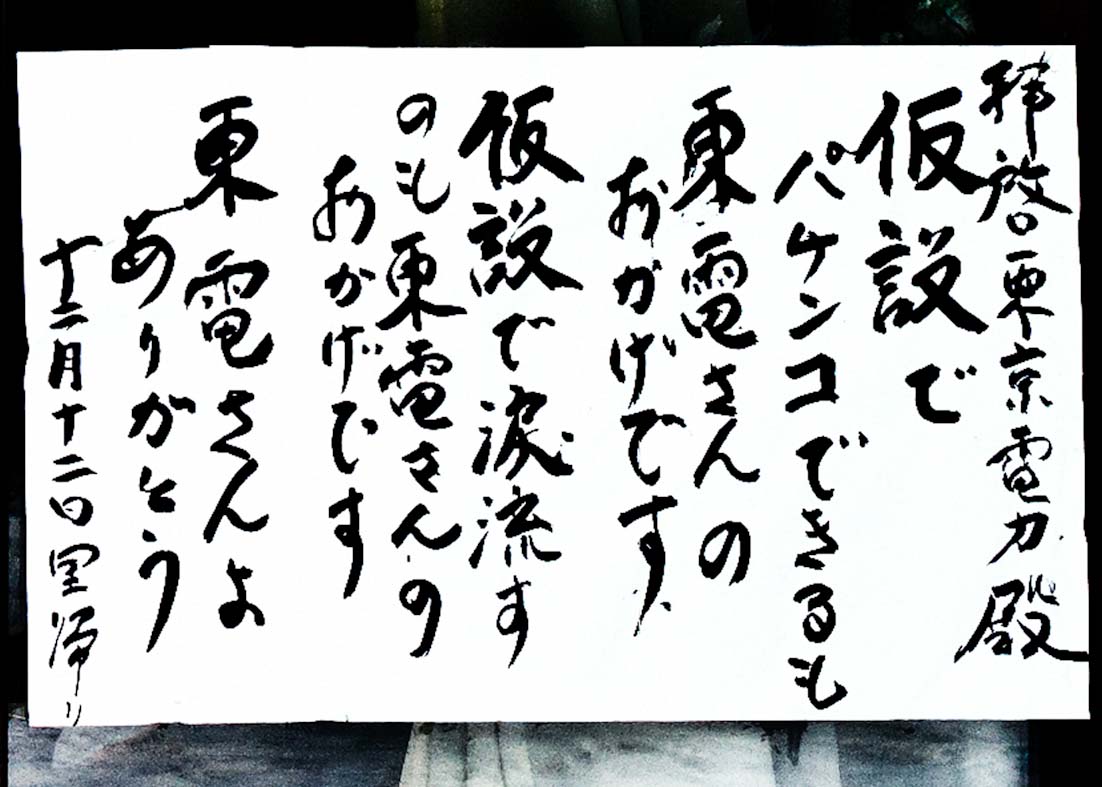

Protesting Against TEPCO – Fukushima One Year Later

Dear TEPCO,

Thanks to TEPCO san,

I enjoy playing pachinko.

Thanks to TEPCO san,

I shed tears in temporary housing.

Thanks a lot man, TEPCO san!!!

jan smith | photography

Comments are closed.