Battle of Balaclava – Prologue

The Battle of Balaclava is one of the most famous battles of all time, despite being a comparatively minor engagement in the Crimean War. The futile heroics of the soldiers who fought there may have gone relatively unnoticed if not for a picture and a poem.

The battle itself is fraught with anecdotes and personalities that combine to make legend. The events of October 25th, 1854 evolve like the episodes of a Greek tragedy, with the fate of the soldiers hinging on the acts of a handful of characters.

Balaclava Episode 1 – The Thin Red Line

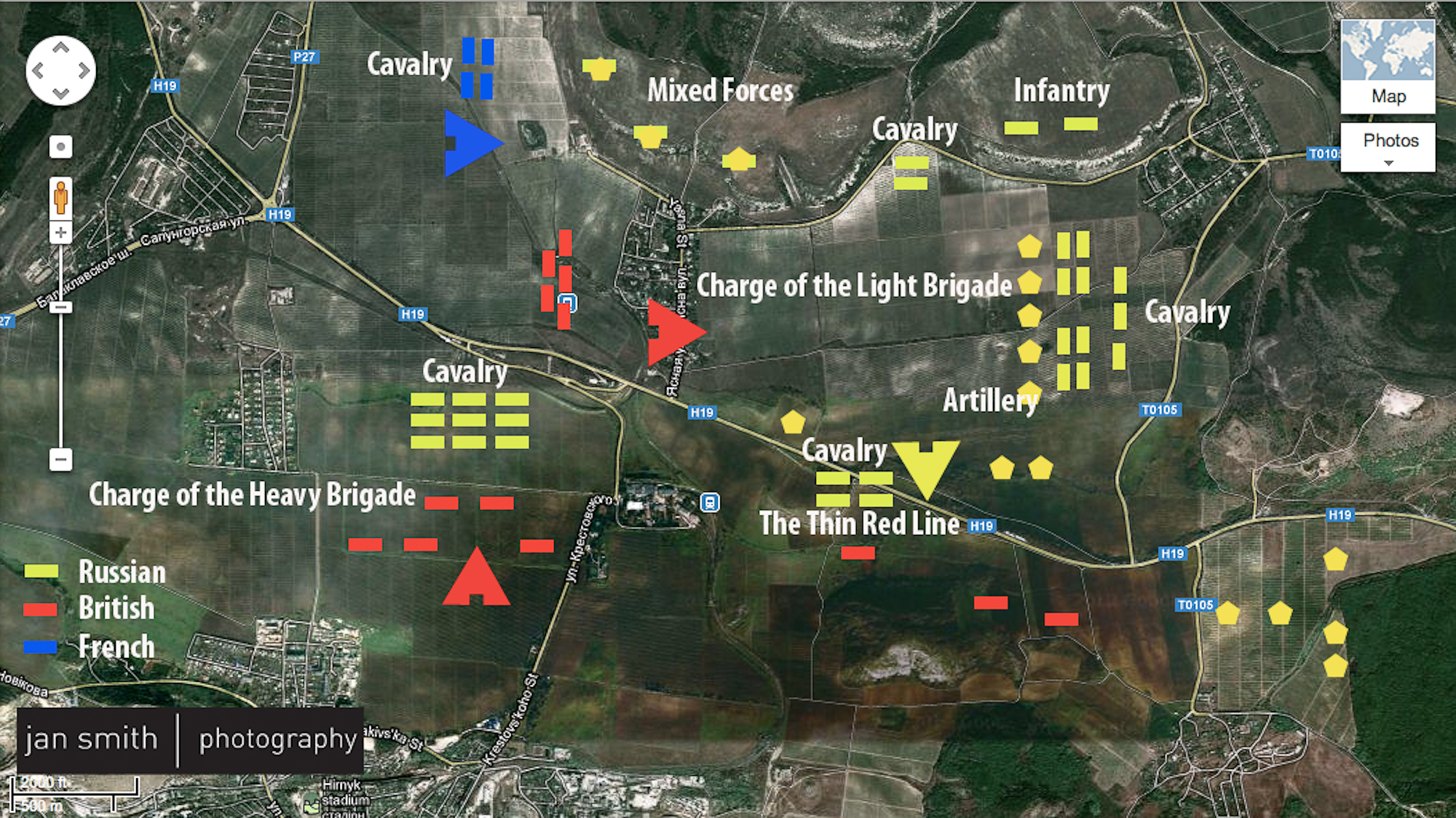

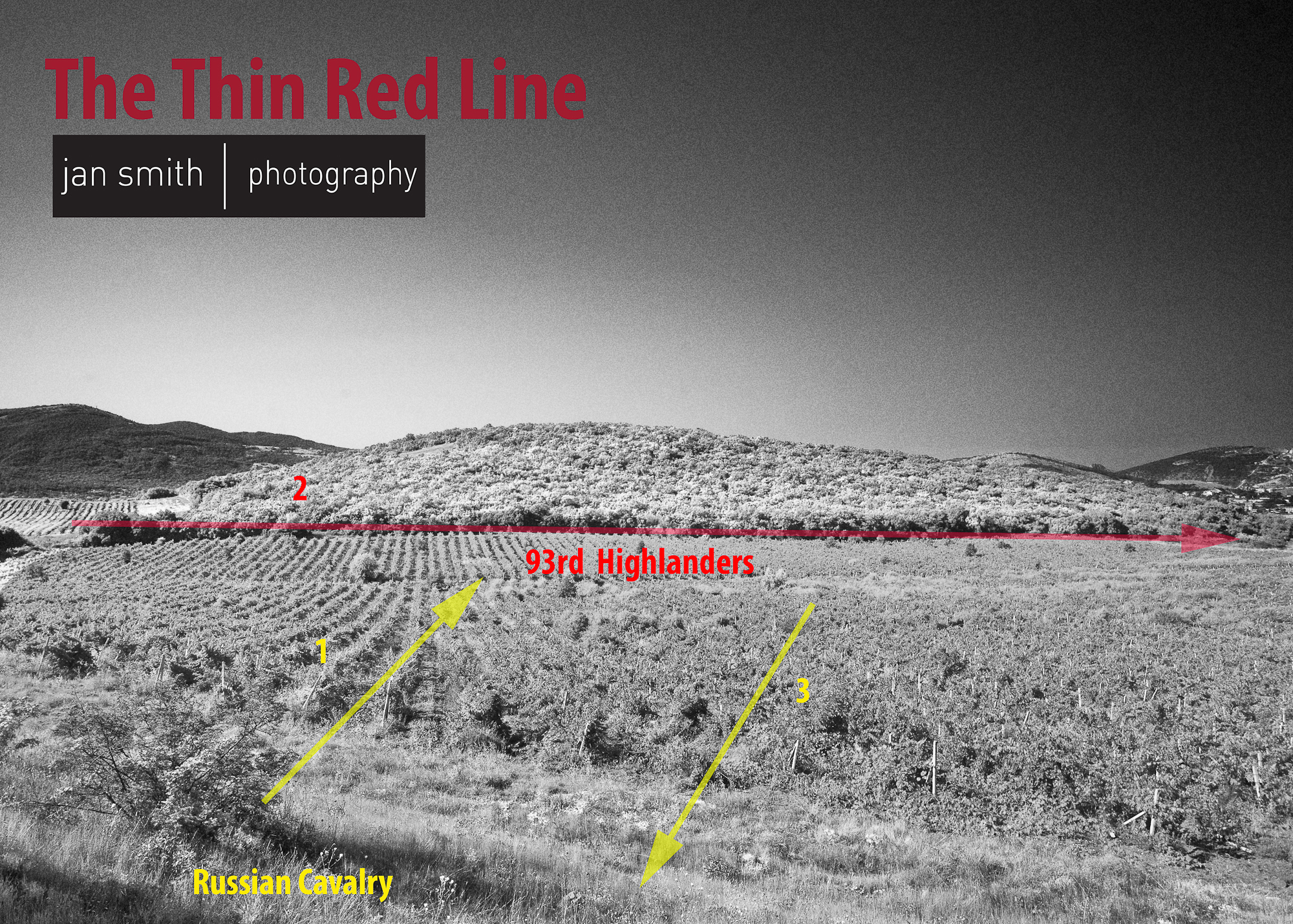

On the morning of the 25th, the Russians overran the Turkish outposts and advanced directly toward the port of Balaclava. The British, who were commanded by Sir Colin Campbell, were late in responding: the divisional commanders were reluctant to tire their soldiers on what they initially thought was a false alarm. The only British troops between the Russian force and the port were the two cavalry brigades which had their encampments in the valley, the 93rd Highlanders, and a small force of marines.

The commander of the 93rd ordered his men to stand firm and hold off the Russian cavalry with no thought of retreat. They were spread thinly across a mile of terrain, their red coats easily visible through the vineyard they used as cover. They put-up an admirable defense that was described by William Russell, correspondent for the Times newspaper, as a “thin red line”. Had the Russians pressed their numerical advantage it is likely they would have broken through the line of the 93rd and captured Balaclava. Instead, they desisted and retreated to the strategically safer high ground of the Causeway Heights.

Balaclava Episode 2 – The Charge of the Heavy Brigade

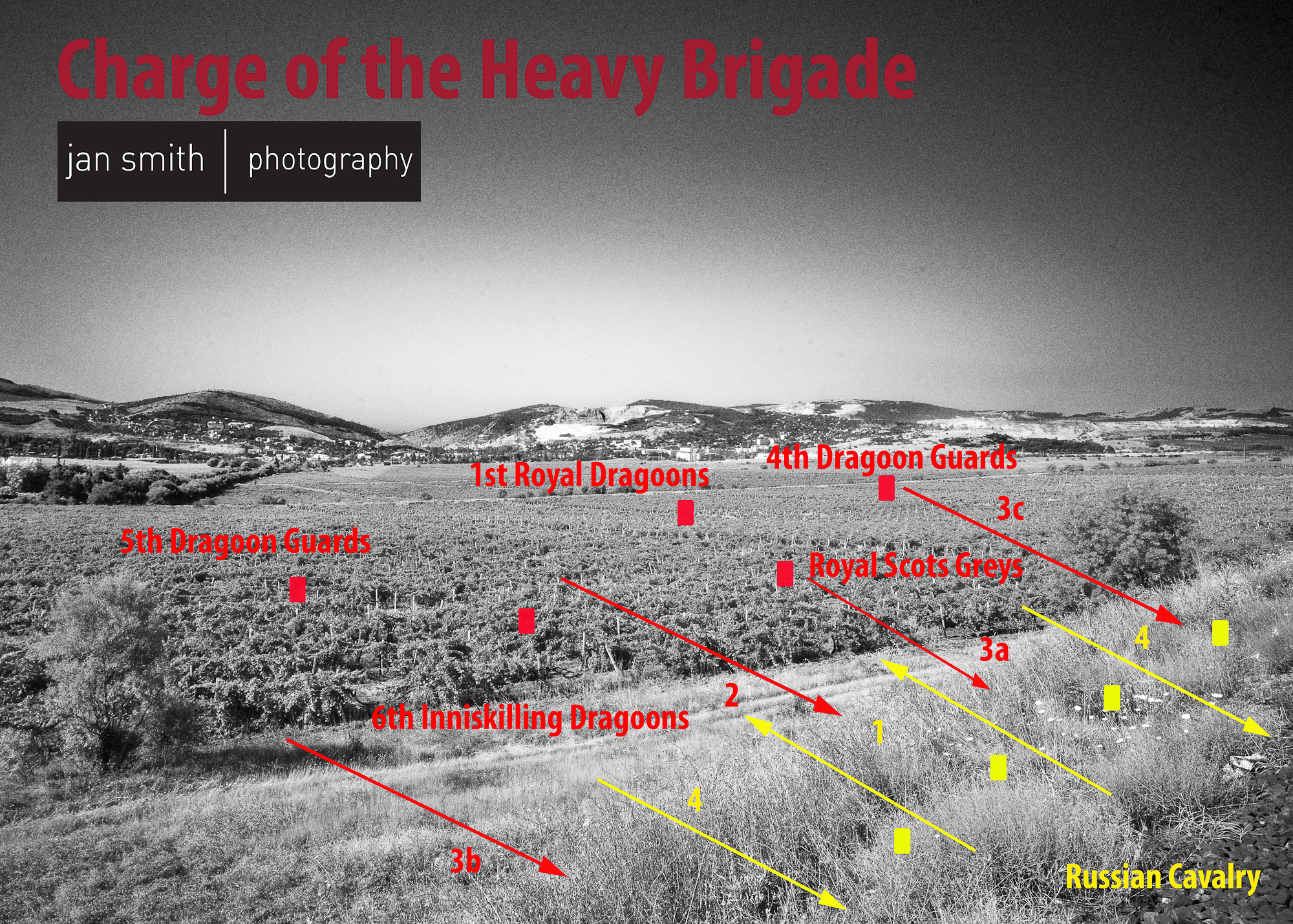

To the left of the 93rd Highlanders a force of Russian horse soldiers was moving over the Causeway Heights towards the British camp. The British quickly mustered six squadrons of heavy cavalry from the Royal Scots Grays, the Inniskilling Dragoons and the Dragoon Guards, but were at least twice outnumbered by the Russians. To add to the precarious predicament, the British commander, General Sir James Scarlett had never commanded troops in battle. He organized his men as if on a parade ground and ordered a charge against the advancing enemy line. To everybody’s surprise, the inferior army hacked and hawed its way into the Russian center with such fury that the larger force retreated back over the Causeway Heights.

Balaclava Episode 3 – The Charge of the Light Brigade

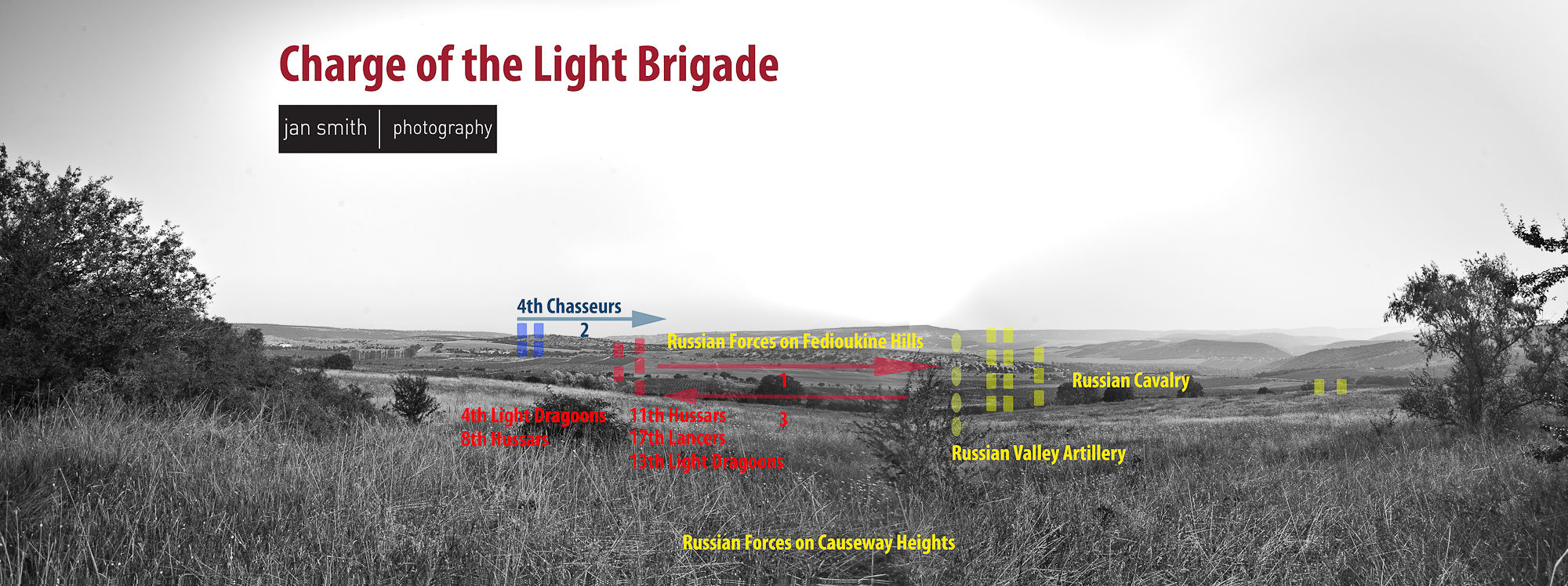

The retreating Russian cavalry was vulnerable to attack from the British Light Cavalry Brigade, under command of Major General the Earl of Cardigan who in turn reported to Lieutenant General the Earl of Lucan. Some historians claim Cardigan and Lucan were brothers-in-law who disliked each other intensely, and that this may have contributed to the tragic miscommunication: instead of sending the Light Brigade after the routed Russian Cavalry, they were sent against the well positioned artillery and cavalry battalions in the valley behind the Causeway Heights. Cardigan and Lucan mutually accused each other of botching the orders.

The events that followed significantly enhanced the reputation of the British Light Cavalry. Armed with pistols and sabers, 673 men and horses charged against Russian artillery lines at the end of the valley. They ran across the low ground for a mile, sustaining fire from three sides: “Cannon to right of them, Cannon to left of them, Cannon in front of them…” Miraculously, they managed to engage the artillery battalions but were soon forced to retreat back through the valley. Lord Cardigan, who headed the charge himself found himself alone among the artillery and rode back. He was one of the first 195 survivors to reach British lines, where he met Sir George Cathcart and is reported to have said, “I have lost my brigade.”

The French 4th Chaussers were able to overrun the Russian positions on the Fedioukine Hills and provide the retreating cavalry some relief, but the end result was carnage. Marshal Pierre Bosquet, who saw the charge stated, “C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre…c‘est de la folie“.

Balaclava 4: The Stasimon or the Stationary Poem

The ride of the six hundred cavalrymen was penned into poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson within a few weeks of the battle: The Charge of the Light Brigade. “Into the valley of Death, Rode the six hundred,” became household words that at once enveloped the British soldiers in the book of Psalms.

Divided into six parts–one for every hundred who charged–the poem is a gripping ode to wasted bravery. “the soldier knew Some one had blunder’d: Theirs not to make reply, Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do & die,” alludes directly to the futility of questioning suicidal orders and echoes the public inquiries being made of the commanders in the months after the battle.

Balaclava 5 Exode – The Exit Song (or Picture)

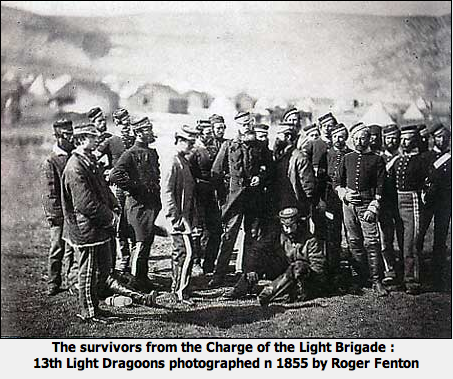

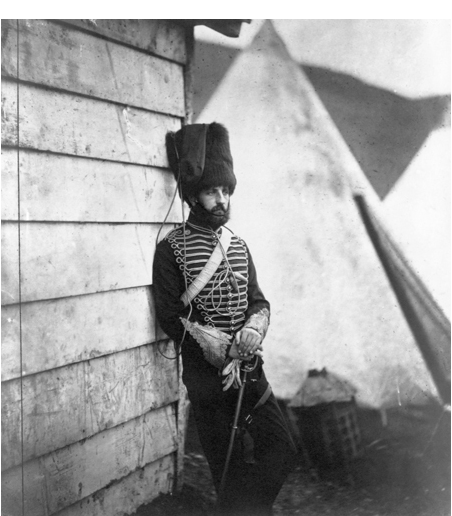

William Russell, the correspondent who witnessed the battle, wrote “our Light Brigade was annihilated by their own rashness, and by the brutality of a ferocious enemy”. Public outcry soon followed and obliged the British crown to attempt propaganda efforts to appease its citizens. The most significant of these actions was the appointing of Roger Fenton as the world’s first official war photographer.

Fenton took a huge amount of equipment, including five cameras and 700 glass plates, plus numerous bottles of chemicals and his own food supply. He transported it all in his “Photographic Van”–really just a converted wine merchant’s wagon. He endured four months of war that included being bombed by the Russians, breaking a few ribs, and frequently suffocating on developer fumes.

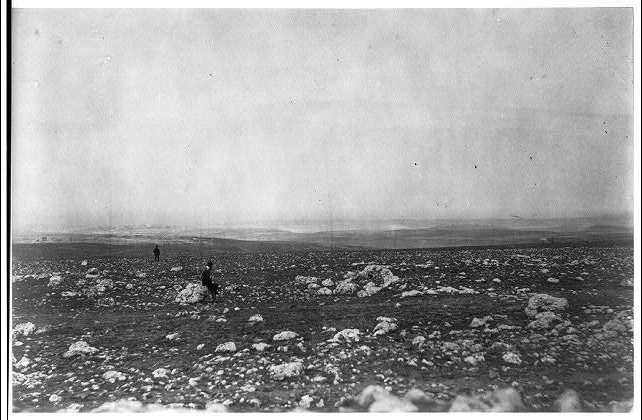

The photographic material of the time limited Fenton to long exposures, and although the ruins of trenches, mutilated soldiers, and corpses were logical still-life subjects, his political mandate limited this choice of motif. Fenton instead focused on the landscape, and of the 350 plates he managed to develop, his most famous one was the one he referred to in letters he sent home as ‘Valley of Death’. The image is iconic not for what is shows, but for what it does not. Beyond the bleak battlefield road littered with cannonballs is the ghost of suffering, an endless road of pain: “Into the jaws of Death, Into the mouth of Hell”…

When exhibited in London in May of 1855, the image’s title was expanded to ‘The Valley of the Shadow of Death’ (as in Psalm 23). The valley depicted is not the one where the infamous Light Brigade charged, but that mattered little because the public already associated the same line in Tennyson’s poem with the debacle of Balaclava. Together, picture and poem set a melancholic mood about war that immortalized the Battle of Balaclava in a light that found glory in defeat.